Aristotle and his successors such as Horace and Geoffrey de Vinsauf set a lot of store by organic form. What do they mean by that?

They all mean that form should fit content. Why? Because Aristotle believes in final causes: he is a teleological kind of a guy. If OOO is going to take Aristotle seriously (and I do, for one), we may have to try a way to have Aristotle without the teleology. Because if there's no top object and no bottom object, then in some deep sense reality is pointless. I know that's a rather harsh way of putting it and it sounds rather nihilistic. And for sure I'm not a nihilist. Nor am I a theist for the record. I think of myself as a non-theist.

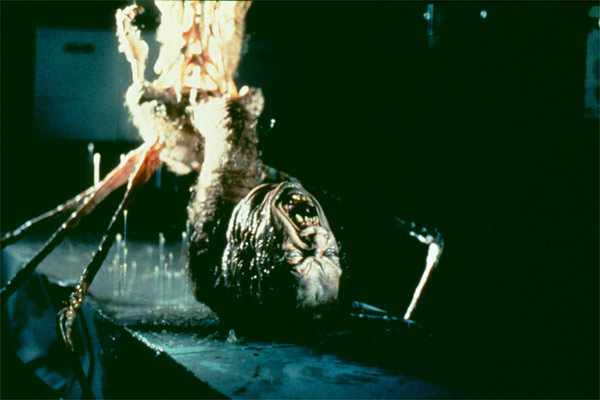

To continue. Reality has no reason, if you like that better (like falling in love). If it's a not-all set, if there's no totality without distortion, if, in other words, any totalizing view is always some kind of sensual object parody of the real, which is proximate, intimate, jumbly strange strangers—if that is the case, then reality is monstrous.

OOO reality is made of objects. These objects consist of other objects. We can assume that that these objects are monstrous. And when we study evolution what do we find? Monstrosity everywhere we look. What's more, these objects, consisting of other monstrous objects, can form monstrous affiliations with other monstrous objects in any which way. Everywhere you look, monsters. (Bryant just posted very effectively on this topic.)

This was Darwin's big discovery, and we're still not used to it. He found it was impossible to distinguish between species and variant, and between variant and monstrosity. Then genomics assures us that lifeforms are monstrous all the way down. DNA itself is a monstrous kluge of mutatations, hybrid code insertions, retroviruses, existing alongside and exchanging parts with plasmids, virions, viroids and all the rest. (One of the main themes of The Ecological Thought.)

All lifeforms are chimeras by definition. That's what evolution guarantees. Your lungs evolved from swim bladders in fish. Do you seriously think that they “wanted” to do that or that they were “meant” to do that, or that that's what swim bladders were really “for”?

Now species is a central concept in Aristotle's teleological conception of substances. The final cause of a substance answers the question “What is this for?” In particular, lifeforms. Rabbits are for digging holes, frogs are for croaking. This means that lifeforms are in no sense monstrous.

A poem, in Aristotle's wonderfully physical way, is a substance. This means that, for Aristotle, it's for something. Elegies are for weeping. Comedies are for laughing. Tragedies are for catharsis. And so on. So poems can't be monsters either. A poem should be consistent with its telos. You shouldn't have funny bits in an elegy. You shouldn't have a horrible murder in the middle of a comedy. Now you know what organic form is.

Horace puts it best. Wow. What a great beginning for a poem, Ars Poetica:

If a painter had chosen to set a human head

On a horse’s neck, covered a melding of limbs,

Everywhere, with multi-coloured plumage, so

That what was a lovely woman, at the top,

Ended repulsively in the tail of a black fish:

Asked to a viewing, could you stifle laughter, my friends?

Believe me, a book would be like such a picture,

Dear Pisos, if it’s idle fancies were so conceived

That neither its head nor foot could be related

To a unified form. ‘But painters and poets

Have always shared the right to dare anything.’

I know it: I claim that licence, and grant it in turn:

But not so the wild and tame should ever mate,

Or snakes couple with birds, or lambs with tigers.

Weighty openings and grand declarations often

Have one or two purple patches tacked on, that gleam

Far and wide, when Diana’s grove and her altar,

The winding stream hastening through lovely fields,

Or the river Rhine, or the rainbow’s being described.

There’s no place for them here. Perhaps you know how

To draw a cypress tree: so what, if you’ve been given

Money to paint a sailor plunging from a shipwreck

In despair? It started out as a wine-jar: then why,

As the wheel turns round does it end up a pitcher?

In short let it be what you wish, but whole and natural.

Isn't that just incredible? And, in terms of my OOO, quite quite wrong. Nothing is “whole.” Nothing is “natural.” To be whole or natural would require some kind of top or bottom object to act as a normative one for all the others. Or some kind of transcendental signifier to set them all straight. But OO reality as Levi Bryant very powerfully argues is a not-all set.

I mean, isn't it also the case that the reason why this is such a great way to begin a poem is precisely because of the rule-breaking? All of a sudden, up rear all these monsters, without a moment's warning?

Isn't that the best way to begin a poem? Isn't that in a sense the only way a poem ever begins? In the strict sense that “aperture” (a technical term for the feeling of beginning) is precisely a feeling of uncertainty, of not knowing, of having no criteria for what counts, yet.

Think about those first few moments of a movie: who's the lead character? Where are we? When are we? It's as if Horace prolongs this uncertainty. He makes his poem begin, with a vengeance. So in a funny way, his monstrous chimeras are indeed beautifully suited in their very ugliness to this part of his poem. (He's full of tricks like that, where form enacts content.)

OOO reality is like a disturbing, ugly Expressionist painting or a cabaret style piece like Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire, full of crowding faces and weird makeup. It's totally stuffed full of monstrous objects.

And if causality runs on the fuel of the aesthetic, we need to investigate the properties of this monstrosity quite carefully.

2 comments:

if all things are monsters, they are also hybrids, mash-ups and boundary breakers - with exuberant overflows and transgresive fangs. they exceed and intervene, explode out from and parasitically induce. In short, doesn’t this show that we live in a vulnerable, fleshy and connected world as opposed to a mosaic of tidy packets and discrete perfections?

I also witness the monstrosity of things…

There's a point in Howl's Moving Castle where Howl's in some distress – I believe he's just seen that his hair's been accidentally dyed black – and he's distracted and bemoaning his situation and is beginning to ooze a greenish liquid all over his body. I mean, he's acting like his life is over. Sophie sees and hears this and will have none of it: "Such drama."

I feel a bit like this with respect to all this talk of how OOO presents us with a world filled with monsters and chimeras and squishy cephalopod-like objects. Why all the drama? It's only the world, nothing more, nothing less.

FWIW, my captcha is "oonic." Sounds like a term of ontological art.

Post a Comment