A digital sampler executes its task several thousand times a second. Nowadays about 48 000 is quite standard. Sample too infrequently and you get aliasing—the sound becomes jagged in various ways.

Sample enough and the sound is smooth—enough. This means that what you hear coming out of a computer is perforated to say the least. Then of course it's compressed in various ways to become AIF, MP3, or whatever.

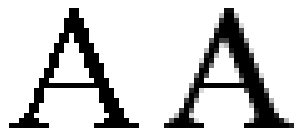

This is one reason why some people still swear by vinyl that's been recorded using analog techniques. They prefer the sound of the analog medium to the non-sound of the perforations. Many of us however have grown accustomed to what is in effect a kind of sonic pointillism in which each bit of sound is precisely regular.

Seurat

SeuratDigital sound technology has given rise to confusion. My uncle, for instance, got into an argument with me about CDs. Now he's a very smart guy who just retired as as biochemistry professor at the University of London. But for the life of him he couldn't figure out how a CD player, or even a CD, could tell in advance whether the sample was an oboe sound or a cello sound. “How does it know?”

Aren't we in general asking the very same kind of question about minds? This isn't about materialist or reductionist theories of mind vs. qualia or whatever. It's about the perfectly straightforward OOO idea that the mind is a sensual object that consists of samples other objects. Versus the idea of mental maps or some mysterious mechanics of intentionality. True Brentano style intentionality would, in my lingo, be a sample.

Given that I have a hunch that causality works through sampling, the issue is even bigger than thinking about mind.

3 comments:

excellent post. I've enjoyed this (w)hole series today. The brain would have it's own sampling rates, right? For instance our sense of taste perceives bitterness with greater precision than sweetness. But either way, it's a sampling rate. I completely agree that the experience of continuity is sensual. It is possibly some kind of evolutionary adaptation. That is, while all objects enter into relations, perhaps the experience of continuity as part of relation is not necessary for all objects. Not sure.

In any case, the expressive/sensual dimension of object relations produces this kind of smooth, whole space: a wall of sound (for a different Beatles reference). Even though materially sound is holey, affectively/sensually it is whole. Is that how you see it?

Hey thanks Alex--a lot of good points compressed. I shall think on them.

For some reason this post reminded me of one of the more intriguing things I have come across in my research about sound and listening. It comes from an article by Mary Russo and Daniel Warner "Rough Music, Futurism, and Postpunk Industrial Noise Bands"and for your Uncle. The sentiment is fairly common now, but I think the use of psychoacoustics is interesting in the cultural context of postpunk noise and of your recent writing on pulse, rhythm, vibration:

Noise components at the beginning of musical instrument tones (usually no longer than a few milliseconds in duration), referred to attack transients, very often provide the primary perceptual clues for aural identification. Without these noise components it is virtually impossible for a listener to differentiate between, for instance, a clarinet and piano tone sounding at the same frequency, because their pitched or "steady-state" portions (comprising most of an instrumental tone's duration) happen to be timbrally similar. In fact, no acoustic instrument or concrete sound is actually a "pure tone". It is possible to electronically produce pure pitch (sine wave) or pure noise (white noise). But aside from these two esoteric exceptions, the entire sound world is one in which periodic and non-periodic vibrations intermingle in an endless variety of ways" (61).

Post a Comment